Pirates of the Aegean

OK - not just of the Aegean, but also the Mediterranean, and the Libyan Sea or South Cretan Sea, because Pirates of the Mediterranean,… is quite a mouthful!

In planning our trip, Caroline and I had a long talk about potential content for my blog, and her interest in filming shorts. Discussion between us included topics like treasure hunting, finding Atlantis, visiting and highlighting less well-known archaeological sites and museums, and eventually to the topic of pirates.🏴☠️ Being a former naval officer who has also done a fair amount of research on ancient ships and sailing, the latter topic seemed intriguing.[1]

Arrrr - my previous life as a pirate (at Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, 2010) - photo by K. Rakuc

To help narrow down sites to visit on our upcoming trip to Crete, I thought I should do a little digging.⛏️😉

“Crete has seduced archaeologists for more than a century, luring them to its rocky shores with fantastic tales of legendary kings, cunning deities, and mythical creatures.”

The above quote rings true for myself and for Caroline. I think we both found Crete to be an absolutely mysterious and wonderous place. Hence the incredible desire to return!

I started my research and noted several ancient references refer to Crete and piracy including (among others) Homer, Thucydides, Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus.

From the time of Homer, 8th century BCE Greek poet, we have the following description of Crete in The Odyssey.

“There is a fair and fruitful island in mid-ocean called Crete; it is thickly peopled and there are ninety cities in it: the people speak many different languages which overlap one another, for there are Achaeans, brave Eteocretans, Dorians of three-fold race, and noble Pelasgi. There is a great town there, Cnossus, where Minos reigned who every nine years had a conference with Jove himself.”

Crete is truly a lovely place with rocky shores, hidden coves and spectacular beaches. When I was there last time I really didn’t want to leave. However, as an island Crete would have been a target of and perhaps a haven for pirates.

Thucydides, a 5th century BCE historian and Athenian general, speaks of piracy on both the mainland and the islands of Greece.

“With respect to their (Hellas) towns, later on, at an era of increased facilities of navigation and a greater supply of capital, we find the shores becoming the site of walled towns, and the isthmuses being occupied for the purposes of commerce, and defence against a neighbor. But the old towns, on account of the great prevalence of piracy, were built away from the sea, whether on the islands or the continent, and still remain in their old sites. For the pirates used to plunder one another, and indeed all coast populations, whether seafaring or not.”

Reference to pirates being utilized by Egypt is spellled out by the 5th century BCE historian Herodotus, who makes mention of “men of bronze coming from the sea” (2.152.3) when Psammetichus (i.e. Psamtik I) confers with an oracle at Buto. The Egyptian pharaoh recruited these Ionians and Carians, who were “voyaging for plunder” (2.152.5).

Notably, Thucydides also credits King Minos (of Crete) for establishing a navy, and freeing “the seas of pirates as much as he could”. (Thucydides, 1,4) Of course, there is still an ongoing debate whether the Minoans had a navy or not, due in good part to the term used by Thucydides of a Cretan ‘thalassocracy’.[2] At the time that Stirling Dow wrote, ‘The Minoan Thalassocracy’, the assumption stood that the Minoans would collect tribute and trade where they could, and where they couldn’t they would ‘turn pirate’[3]. (Dow, 1967: 14)

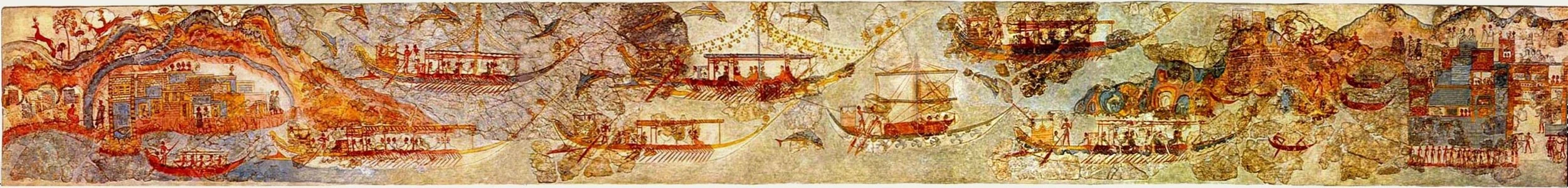

For what that navy may have looked like, there is a wonderful fresco of ships from the Minoan site of Akrotiri, on Santorini. They have been described by Raban [4] as follows:

“The Theran craft are long ships, powered mostly by sail, that could fulfill several functions. They are designed to navigate the estuaries that were characteristic of the Bronze Age Mediterranean coasts. These ships could sail stern-first, be moored in deep water and sustain combat in open water. Their major use was probably for robbery and piracy.”

Bronze Age fresco of a ship procession from Akrotiri on the Aegean island of Thera (Santorini). From Room 5 of the West House, c. 2000-1500 BCE. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

Diodorus Siculus [5] credits the piratical activity of Crete for the start of the First Cretan War.[6]

“With a fleet of seven ships the Cretans began to engage in piracy, and plundered a number of vessels. This had a disheartening effect upon those who were engaged in commerce by sea, whereupon the Rhodians, reflecting that this lawlessness would affect them also, declared war upon the Cretans.”

Perlman’s 1999 paper [7] however argues that “Diodorus’ account of the First Cretan War probably depends on Polybius, who in turn relied upon a Rhodian source or sources, most importantly Zeno’s history.” Regardless, there seems to be sufficient evidence that piracy in or from Crete was mentioned by numerous sources (biased or not).

The Archaeology

In 2003, Elpida Hadjidaki and her team discovered the first Minoan ship off the island of Pseira, close off the northeastern coast of Crete. Excavations were carried out on the site from 2003-2009 and the findings were published in 2021.[8] Many of the artifacts from this shipwreck are now stored at the Archaeological Museum of Siteia, in eastern Crete.

The Minoan Shipwreck at Pseira, Crete

Book cover - archaeological report

Other evidence for Minoan trade and shipping comes from a second Minoan ship which was discovered in 2009. A research team under the direction of the archaeologist Elias Spondylis, made this important discovery in the Koulenti area, on the Laconian coast (southern Peloponnese). [9] And another Minoan merchant ship was discovered in the Marmaris Hisarönü Gulf, Turkey in 2016. [10] In 2024 Turkey reported a 3,600 year old Minoan dagger was found on a shipwreck off the coast of Antalya - furthering proof of connectivity.[11]

Locations in Crete that may be linked to piracy or anti-piratical defenses include the following:

Phalasarna was a harbour town located at the very western cape of Crete. “Because of the impressive size and extent of the fortifications around its harbor, it is often assumed to have been one of the many Cretan cities whose revenues were primarily derived from piracy during the Hellenistic period.” [12] It appears the site was destroyed “during the Roman suppression of Cretan piracy under Metellus Creticus.” [13]

Imeri Gramvousa is a small island where 17th and 19th century (CE) guns were located in the reef, and “the islet was used as a base of rebels that were pirating the area.” [14] There was a Venetian [15] fort which was built on the island in the late 1500s. During the Greek War of Independence the island was attacked by the Ottomans. “The insurgents were besieged in Gramvousa for more than two years and they had to resort to piracy to survive. Gramvousa became a hive of piratical activity that greatly affected Turkish-Egyptian and European shipping in the region.” [16]

Map of Imeri Gramvousa

Scoglio, et Fortezza delle Garabuse - Francesco Basilicata - 1618

During the Hellenistic period, Hierapytna [17] was specifically named as being the city who started the First Cretan War with Rhodes (SIG 567 - see quote below).[18]

“...since after the inhabitants of Hierapytna wickedly started a war against our whole people, the warships and light ships were manned...”

Hierapytna was also the last city to surrender during Metellus' conquest of Crete (66 BCE).[19]

“Aristion had just withdrawn from Cydonia, and after conquering one Lucius Bassus who sailed out to oppose him, had gained possession of Hierapydna. They held out for a time, but at the approach of Metellus left the stronghold and put to sea; they encountered a storm, however, and were driven ashore, losing many men. After this Metellus conquered the entire island.”

From the Minoan period up until and including the Ottoman, there appears to be sufficient evidence to support the claim of piratical activity in the Mediterranean, associated with Crete or other islands, but significant enough to have both historical and archaeological records.

Map of mentioned sites in Crete

At least from our point of view (and our limited time on this trip) I think we will have time to check out the sites in Western Crete. I plan to share some commentary and photos from Phalasarna and Gramvousa upon my return. If you have any questions or suggestions, please share them in the comments section below.

[1] I served as a Canadian Naval Officer from 1989-2000, and a Board member of the International Association of Maritime Security Professionals from 2011 to 2022.

[2] thalassocracy - from the Ancient Greek: θάλασσα thalassa meaning ‘sea’, and κρατεῖν, kratein, meaning 'to rule' or ‘power’

[3] Dow, S. (1967) The Minoan Thalassocracy. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 79, 3–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25080631

[4] Raban, A. (1984) The Thera Ships: Another Interpretation. American Journal of Archaeology, 88(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/504594 p. 18

[5] Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History. Published in Vol. XI of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1957. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/27*.html

[6] First Cretan War refers to the war between Rhodes and Crete in 205-200 BC. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cretan_War_(205-200_BC)

[7] Perlman, P. (1999) Krētes aei Lēistai? The Marginalization of Crete in Greek Thought and the Role of Piracy in the Outbreak of the First Cretan War, in V. Gabrielsen et al. (eds.), Hellenistic Rhodes: Politics, Culture, and Society. Aarhus University Press.

[8] Noteworthy for Caroline and I, Todd Whitelaw (who was the director on the survey we conducted at Knossos in 2008) is a listed author, who worked on and co-authored a chapter on the ceramics from the ship. https://profiles.ucl.ac.uk/1012-todd-whitelaw/publications ; see my blog post Minoan Adventures.

[9] Kommos Conservancy (2013) A Lakonian (Minoan?) Shipwreck. Posted online Jan. 15, 2013; and Spondylis, E., Lolos, Y. G. and Marabea, Chr. (2017) A new Minoan shipwreck from the era of the Thalassocracy at Koulenti, off the Laconian coast in southern Greece, Under the Mediterranean, The Honor Frost Foundation Conference of 'Mediterranean Maritime Archaeology', Nicosia, 20-24 October 2017.

[10] Holloway, A. (2016) 4,000-year-old Minoan shipwreck discovered in Turkish waters. Ancient Origins. Posted online Jan. 31, 2016.

[11] Radley, D. (2024) 3,600-year-old Minoan bronze dagger unearthed from ancient shipwreck off the coast of Antalya. Archaeology News Online Magazine. Posted online Sep. 1, 2024.

[12] Frost, F. J., & Hadjidaki, E. (1990) Excavations at the Harbor of Phalasarna in Crete: The 1988 Season. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 59(3), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.2307/148300 p. 513

[13] Ibid p. 525; Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quintus_Caecilius_Metellus_Creticus

[14] Theodoulou, T., Foley, B., Tourtas, A. (2018) Western Crete Project, 2013: Preliminary Report. Underwater survey at Kissamos Bay and the promontories of Rhodopos and Gramvousa. In A. Simossi (ed.), Diving into the Past. Underwater Archaeological Research, 1976-2014, Athens, 6th March 2015, Athens: Fund of Archaeological Proceeds, 305-312. p. 309

[15] Venetian Crete (1205–1669)

[16] Gramvousa - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gramvousa ; I just happened to learn about Gramvousa when I was looking into information about Balos Beach after reading a recent article about “10 of the best beaches in Greece” - Litson, J. (2025) 10 of the best beaches in Greece – and where to stay nearby. AOL. Posted online May 13, 2025.; For a tour guide’s perspective on Balos and Gramvousa, I recommend this video by ‘Greece Explained’ - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHhVf05j2qo

[17] Hierapytna, lies beneath the modern city of Ierapetra, “and so it is difficult to trace the settlement history of the site.” (Perlman, 1999: 143)

[18] Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum: 567 - Kalymna Honours Lysandros - Greek text: TitCal_64; Date: c. 204/1 B.C.; Segre, Mario, “Tituli Calymnii.” In: Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente (ASAA) (Bergamo; Rome). 22-23, N.S. 6-7, (1944-1945 [1952]), pp. 1-248. https://www.attalus.org/docs/sig2/s567.html

[19] Cassius Dio, Roman History 36.19 - https://lexundria.com/dio/36.19/cy

Other References

Abell, N. (2023) The Myth of the Minoan Thalassocracy: A Review of Evidence for Maritime Interaction, Power, and Violence in the Insular and Coastal Aegean. In Lynne A. Kvapil and Kim Shelton, eds., Brill's Companion to Warfare in the Bronze Age Aegean. Ch. 10, pp. 353-417.

Aed, N. (2024) 3,500-Year-Old Advanced Minoan Technology Was ‘Lost Art’ Not Seen Again Until 1950s. Ancient Origins. Updated online Sep 10, 2024. https://www.ancient-origins.net/history/3500-year-old-advanced-minoan-technology-lost-art-not-seen-again-until-1950s-009899

Blumberg, A. (2013) Piracy in Archaic and Classical Greece. Karwansary Publishers. Posted online August, 2013. https://www.karwansaraypublishers.com/en-ca/blogs/ancient-warfare-blog/piracy-in-archaic-and-classical-greece#

Bonn-Muller, E. (2010) First Minoan Shipwreck: An unprecedented find off the coast of Crete. Archaeology, Vol. 63, No. 1. https://archive.archaeology.org/1001/etc/minoan_shipwreck.html

W. L. Friedrich, W.L., Højen Sørensen, A., Katsipis, S. (2015) The Ship Fresco from Akrotiri, Santorini Traveler, June-August 2015, 14-15

Giesecke, H. E. (1983). The Akrotiri ship fresco. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 12(2), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-9270.1983.tb00121.x

Goodyear, M. (2021) The Medieval Pirates’ Nest of Crete. Medievalists.net. https://www.medievalists.net/2021/12/the-medieval-pirates-nest-of-crete/

Hadjidaki, Elpida, Betancourt, P., Brogan, T., Cutler, J., Dierckx, H., Nodarou, E., Whitelaw, T. (2021) The Minoan Shipwreck at Pseira, Crete. In Prehistory Monographs. INSTAP Academic Press.

Hadjidaki, E. (1988). Preliminary Report of Excavations at the Harbor of Phalasarna in West Crete. American Journal of Archaeology, 92(4), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.2307/505244

Herodotus, Histories. An English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hdt.+2.152&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126

Hitchcock, L.A., Maeir, A.M. (2018) Pirates of the Crete-Aegean: Migration, Mobility, and Post-Palatial Realities at the End of the Bronze Age. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of Cretan Studies, Heraklion, 21-25 September 2016, Heraklion: Cretan Historical Society.

Homer, The Odyssey. English translation by Samuel Butler (1900). Project Gutenberg. Last updated Dec. 2, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1727

Nowicki, K. (2001) Sea Raiders and Refugees: Problems of Defensible Sites in Crete c. 1200 B.C. In V. Karageorghis and C. Morris (eds.), Defensive Settlements of the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean after c. 1200 B.C., Nicosia 2001, 23-39.

The Maritime History Podcast - Ep. 012 – Minoan Thalassocracy; Ep. 013 – Akrotiri, Atlantis, and the Thera Eruption; Ep. 014 - The Amarna Letters and Some Lukkan Pirates.

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. London, J.M. Dent; New York, E.P. Dutton. 1910. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Thuc.+1.7&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0200

Trakoli, A. (2021) Minoan Art, The ‘Saffron Gatherers’, c1650 BC, Occupational Medicine, Volume 71, Issue 3, April 2021, Pages 124–126, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqab019

White, Joshua M. (2017) Piracy and Law in the Ottoman Mediterranean. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-0392-9.